Five-Paragraph Essay, It’s Time for You to Die

All-right, five-paragraph essay. You and I have struggled long and hard.

In middle school, you rolled up on your Razor kick scooter and, laughing, rubbed my nose on the asphalt. In high school, I fumbled my hand up your shirt and thought I was in love. In college we fought; I’m fuzzy on the details, but the cops were involved, I think.

We have a messy history.

I turned out to be a teacher, in the end. Like you wanted. But I’m not here to thank you.

I’m here to kill you, once and for all.

I know it won’t be easy. Others have tried. Still, you keep coming back, like some unstoppable monster.

But I have a plan.

I’m going to tell everyone about you, Five-Paragraph Essay. The real you. I’m going to tell all your secrets.

You’re Popular Because You’re Easy to Grade.

You will always have your defenders. Teachers who like to argue that you’re like training wheels. A formula to get students steady on the idea of how to structure sustained writing. Then, presumably, another teacher in the future will take the training wheels off–introduce other methods for organizing and developing prose. The five-paragraph essay, argue your supporters, is just one step in the process of acquiring writing skills.

Nice myth.

I know the truth. I know why you are so popular. You’re easy to grade.

See, all a teacher has to do to grade you is compare you against a mental model. What constitutes a “good” paragraph essay is definable in concrete terms. Your intro paragraph has a hook or “compositional risk,” following by a narrowing of the topic, then a thesis statement. Some teachers even put on their rubric whether a kid’s thesis has three prongs. You know, a list of the three topics that will be covered by the body paragraphs. Your body paragraphs have to begin with topic sentences, your conclusion has to restate your thesis.

Pretty easy to slap a grade to an essay following this model. Grade it based on how far it deviates from the form. Because form is easier to grade than content.

It’s easier to assign you, Five-Paragraph Essay, than to assign and grade real writing. Engaging with a students’ choices, the moves they’re making — measuring their appropriateness to a given rhetorical situation, judging the paragraphs’ coherence and cohesion — these tasks take a lot of damn work.

You Don’t Give a Damn about the Kids Who Write You.

Here’s another secret of yours. You could care less who writes you. You could be written by anyone, because you’re always the same. You’ve got people afraid deviating from the pattern. Of even using the word “I” when they write.

You’re not about developing ideas. About using writing to think and refine and come to a new realization. You’re about restating what is already known. So, if all that matters is how correct the content is, how well it reflects what the teacher takes for granted as true? Then you don’t care who is writing it.

Why bother, you’d say. We can’t hope to understand where a student is coming from, what they are bringing to the table, and the source material they are unconsciously synthesizing. Maybe it would be nice in a perfect world. But this isn’t a perfect world; and anyway, who has the time to even try?

Your Life Philosophy is Ass-Backwards.

This brings us to your next secret. Five-Paragraph Essay, you don’t even have a good handle on reality.

You believe the following:

- There is a correct way to develop expository writing.

- That correct way is stable — it doesn’t change.

- That correct way is knowable — the teacher knows it; the student doesn’t.

This is a load of garbage.

I’m not here to debate epistemology with you, Five-Paragraph Essay. Believe what you want about the reality of how we know, how knowing works, how it is passed on. You do you, bruh.

But the teachers out there don’t have the luxury of your sloppy, lazy worldview. Teachers can indulge in positivism at home, sure. But in the classroom, they need to operate from another basis.

In fiction we talk about the willing suspension of disbelief. Aesthetic appreciation of fictional worlds can only happen if the reader chooses to accept. Sure, Superman’s abilities violate the laws of physics. But so what? We accept his powers and enjoy the story.

There’s a similar suspension of disbelief required for teaching. A teacher has to accept the crazy idea that knowledge is fluid. That meanings drift and change. That every individual — including students — can shift the needle. We all have a say when it comes to defining the world. That, in fact —

- There is no set-in-stone correct way to develop expository writing.

- The effectiveness of writing strategies change as culture changes.

- Teachers and students have varying, limited access to the ever-shifting web of available, effective writing strategies.

You’re Not Even a Real Essay.

And here’s the most devastating truth about you. You’re not an essay at all, and never were. You’re too damn organized.

The word “essay” comes from the French essayer, to attempt or try. Montaigne, who invented essays, defined them as rambling attempts to put his mind, his personality, on paper.

Samuel Johnson, the guy who invented the dictionary, wrote essays. He defined the essay this way:

a loose sally of the mind; an irregular undigested piece; not a regular and orderly composition. (1755)

Henry Coupée, a Victorian rhetorician, says essays are

experimental compositions, not pretending to the dignity of a higher order…giving, as it were, only a partial glimpse of its subject; often not promising more; desultory in its arrangements, but novel and suggestive in its statements. (1866)

Sherwin Cody, another professor of rhetoric, put it this way:

The essay, like conversation and letters, has no structure. (1903)

See a pattern? All your obsession with thesis statements, topic sentences, proceeding in a logical order — everything that makes you who you are — has nothing to do with essays.

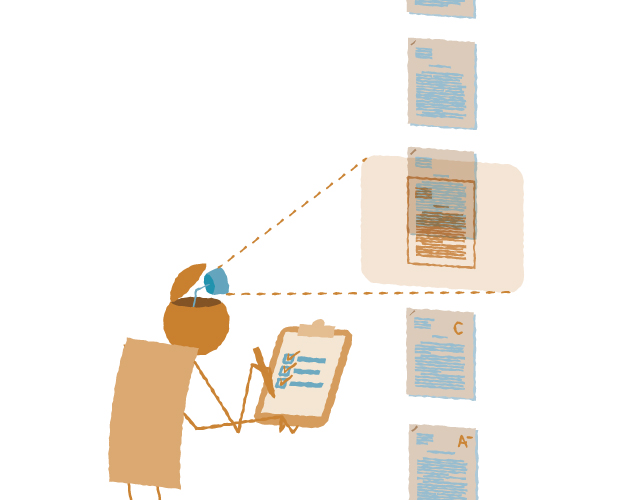

You’re not an essay. Your just a poor excuse for a checklist, dressed up in paragraphs, like a skeleton in a bulky fur coat.

In Conclusion.

Well, Five-Paragraph Essay, this is it. I’ve told everyone how you’re no good for students. How you perpetuate false notions about how writing works, and how learning works. How you aren’t even a real essay.

Look at that. How traumatized I am — you’ve got me summarizing my main points in my conclusion.

Maybe I’ll never be rid of you.

Doesn’t matter.

I will fight you forever.

3 Replies to “Five-Paragraph Essay, It’s Time for You to Die”

Well done. Fight on!

These essays may not be perfect but it would be useless to think that they will be gone in the nearest future..

You’re very right — it will be a knock-down, drag-out fight. It will take long-term commitment to better teaching practices. It will take time.