Writing Poetry: How to Live with Your Terrible First Drafts

You Suck at Writing Poetry.

The first draft is always a failure. If you’ve ever tried writing poetry, I bet you know this.

I have a theory. Lots of people try poetry. Most would sooner admit to watching porn on their lunch break. But they do. They try it, but they get stuck. Because they write a first draft, and it’s terrible. This is inevitable. How someone responds to this truth is important, though.

When faced with your garbage first attempt, you might decide you have no skill as a poet. You might even decide poetry itself, as an art form, is a waste of time.

You might think you’ve written something good. You share this unrevised monstrosity around. This never ends well.

And on the other hand, there’s impostor syndrome. Those who actually are competent at writing poetry feel like they are fakes. Because they look at their first drafts, their terrible, craptastic first drafts, and despair. But then somehow, they get more and more competent, and eventually master their voices and become poets.

How?

They live with the fact that first drafts are garbage. They accept them. They love their crapitude.

And then they revise.

Obvious. Right? But even so, I find most people still would rather live with a lie. The lie that their crappy first draft proves their poetic ineptitude.

It’s Okay. I Suck at Writing Poetry, Too.

I’ve published a few poems, and I’m always sending more out. I’m not a master poet, sure, but I work at it. And still, now matter how hard I work, the rule still applies. The first draft is always a failure. My first drafts are often stinking piles of word vomit.

But that’s okay.

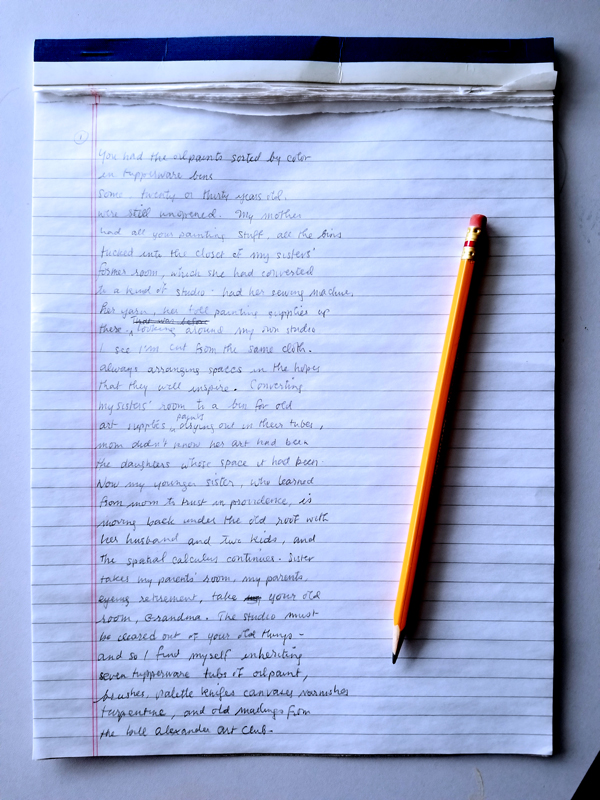

Here’s one from this morning:

I know, you don’t want to try and read my handwriting, shrunk down and compressed in a JPG. You don’t have to. In fact, I’d rather you didn’t. Because it’s a terrible draft. It’s a rambling mess. I mean, I misspelled “knifes,” for crying out loud.

You don’t need to read it.

What I’m trying to say is that I needed to write it.

A couple weeks ago, my mom invited me over. She was clearing out a closet, and, she said, if I was interested in taking any of my grandmother’s old art supplies off her hands, she’d appreciate it.

I already knew, before I responded, that this was a Poem-Prone Moment. Or as they say in Spanish, un momento poemable. They don’t say that in Spanish. I just like adding “-ah-blay” to words. Because I’m a poet.

But my point is, the first step happens before the pencil hits the paper. Sometimes weeks or months or years before. And that step is the itch. The reason to write a poem.

Why Do People Write Poetry, Anyway?

A lot of people screw this part up. They sit down and say, I guess I’ll write a poem. To be honest I don’t know what they say. But they think it’s a matter of capturing inspiration. Or just mucking about until they find something to say. Both methods work, but they are very wasteful of time.

I like how Rilke says it, in a letter to an aspiring poet:

Search for the cause, find the impetus that bids you write. Put it to this test: Does it stretch out its roots in the deepest place of your heart? Can you avow that you would die if you were forbidden to write? Above all, in the most silent hour of your night, ask yourself this: Must I write?

In my mom’s text, I felt it. That itch, that need to write about it. Or it would eat at me. Listen, my grandma’s been dead for twenty years, but we’re still sorting through her stuff. Why? That’s something that needs, like seven Tupperware tubs of oil paints, to be unpacked.

But I didn’t rush.

On Failing Productively.

So, as I said, my first draft was a failure. But it was a great failure. A productive failure. A beautiful failure (like I said about my first try at a logo design for this site).

Why was it a beautiful failure? Because it clarified for me the creative problems I needed to solve:

- Should I list the art supplies that I had to unpack from the closet? (In other words, is the devil in the details?)

- What role should enclosed space (rooms, closets, tubs) play in this poem?

- Is this poem really about the challenges my family is going through? Or about a lingering grief?

Now listen. Those are some deep questions. After writing the draft, and thinking about these questions, I realized something. This poem was going to be hard to write.

But that challenge was only going to feed the itch. Now it was also a puzzle I needed to solve. A puzzle about my family, my self.

So, I let the draft live, even though it’s so bad I would never show it to anyone. Well, except you.

The point.

In the end, I hope you agree that first drafts are bad. There’s no way around it. But that they are necessary. That they need to be accepted, in all their terribleness. Because they do us the great psychological service of identifying the questions we need to answer for ourselves. That doesn’t mean they’ll answer the questions. In fact I think a poem is more worthwhile if it churns up the question and lets it hang.

So, we not only need to get those garbage first drafts out, but we need to push past them. The revision process, this process of refining the question the poem is asking, is the point. It’s the purpose for writing poetry.

The nicely crafted final draft is just a bonus.