What do You Mean, “Analyze?”

So, on the second day of class, I put a poem in front of my sophomore English students.

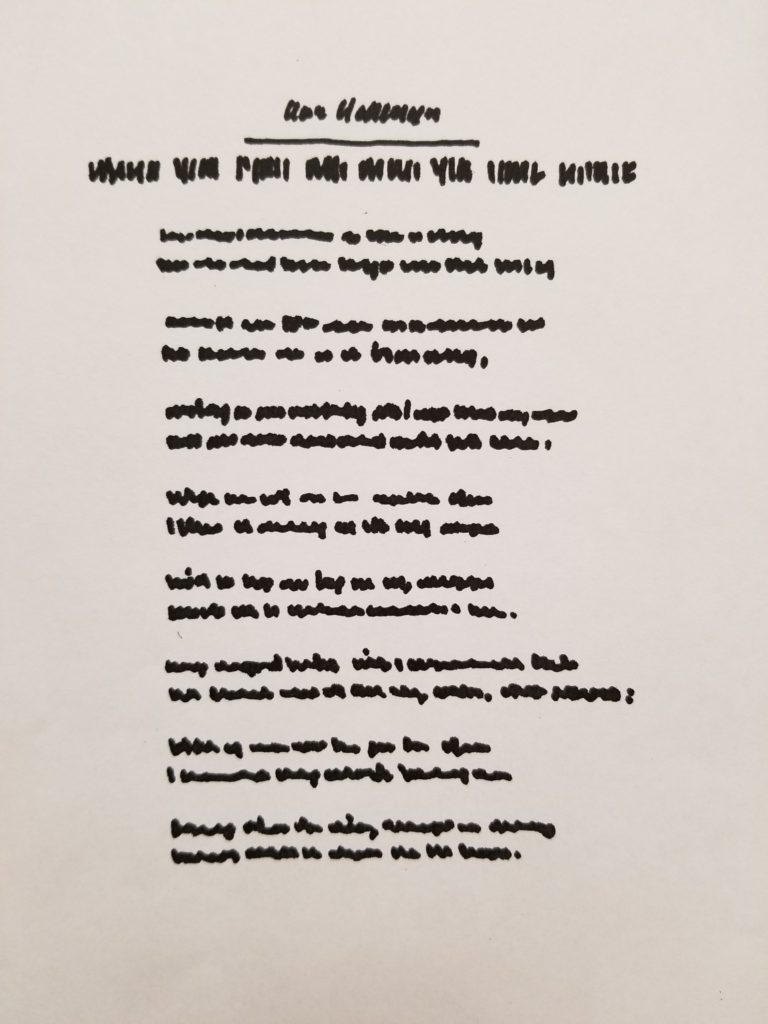

Well, not exactly. I put the shape of a poem in front of them. It looked like this:

I told them, “Take a couple minutes to read this over.” Immediately, they began asking whether or not they were supposed to be able to read it. (They suspected I was up to something.)

I said, “Well, given that you can’t read it, what can you tell me about it anyway?”

The uproar that followed was delicious. Expressions of confusion and frustration and sarcasm — and then through the noise I heard one student say, “It has stanzas.”

“Ah!” I said. I pushed her further. “How do you know it has stanzas?”

She noted the spaces between each pair of lines. Another student asked what a stanza was, and the class whipped up a definition together: sections in a poem separated by spaces.

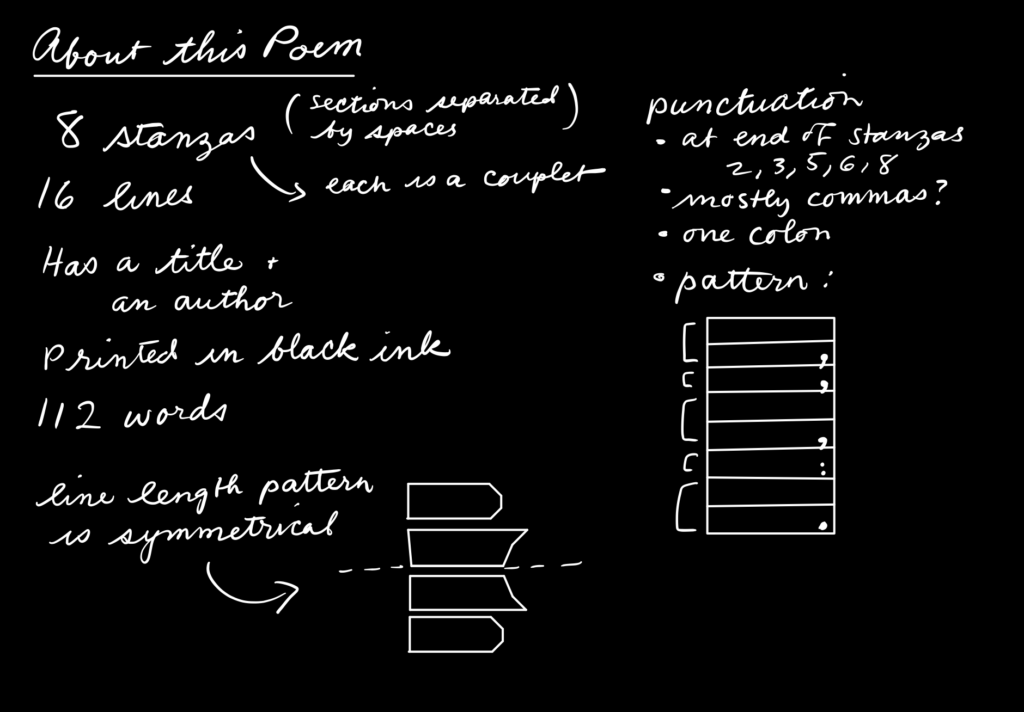

Another student noted that the poem had sixteen lines separated into eight stanzas; then I asked if anyone knew the term for a two-line stanza (someone did — couplet). From there the students dove in and noted the number of words, the placement of punctuation, the symmetrical figure created by varying line lengths, and the pattern implied by the placement of punctuation.

I praised them throughout at their ability to observe and describe many things about a poem they couldn’t even read.

See where I’m going with this?

Meaning is So Distracting

In my experience, the average fifteen-year-old is very fuzzy on what analysis is. What it entails, and what it doesn’t. They constantly interpret, deduce, and predict when I am only asking them to observe and describe.

So I thought, how could I get this class to analyze a poem without skipping and hopping, like stilt-legged llamas into the La Brea Tar Pit, into deep but murky interpretive claims about the poem?

I had to give them a poem without content. I knew that the content would only distract them.

So I found a poem in a back issue of Rattle and traced over it with a Sharpie marker.

Here are the notes from the board, collecting their observations about my contentless poem:

My next step was to ask them to write up their analysis. I said, in a paragraph or a few bullet points, analyze the poem.

Again, they were thrown into confusion — on the one hand, I could have probably phrased the writing prompt more clearly: what I wanted them to do was take our notes from the board and translate them into a document that communicated our observations to a third party — someone who wasn’t in the room for our discussion.

But their confusion actually led us to define analyze in an awesome way.

They kept asking whether I wanted them to write something that built on the notes we took together. I kept insisting if they did, they’d probably get stuck trying to interpret a poem they couldn’t read or understand. They asked if they should work from assumptions; I said we could work from the assumption that it was in fact a poem. This back and forth allowed us to define analysis as organizing and communicating a series of observations after breaking down a subject. Not bad for our purposes.

I asked the class, “On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident were you that you knew what analysis was at the beginning of class?” I got numbers like 0, 2.5, 3. “How confident are you now?” They gave me numbers like 8 and 10.

Remember, You're the Teacher, not the Authority

My students’ success with this activity was actually quite humbling. It reminded me that my definition of analysis was only mine. It wasn’t the definition. And ultimately, if we want to get all social-constructivist, there is no the definition. Only our definition right now.

And that’s the definition of anything (not just analysis) we should be acknowledging and celebrating in the classroom. The definition we arrive at as a community.

I highly recommend this lesson. At the very least, I recommend digging into whether or not your students actually understand what you mean when you use teacher-lingo. Chances are, they don’t. And it’s not their fault; we teachers sometimes use terms like analyze pretty loosely. I’ve heard teachers say analyze when they mean describe. I’ve heard them use analyze to mean interpret. Heck, I’m sure I’ve done this.

I’m sharing this lesson because it’s close to the heart of one of my goals this year: I will trust my students. I realized part of trusting them — of believing they were bringing everything they could to the table, that they were willing and wanted to do well — was being constructivist in my language.

I trust that if I ask them to analyze, they will do their best to analyze. Trusting them also means I believe that any responses that present poorly-developed interpretations and deductions (instead of analysis) are not the evidence of “unreadiness” or a lack of skills or even laziness. Rather, half-baked interpretations are the result of me, the teacher, assuming my language is our language when it isn’t.

Yes — I will trust that they are doing their best. If I’m clear about what I mean when I say “analysis,” their best will get better.

3 Replies to “What do You Mean, “Analyze?””

Love this!

I remember, in one of my first college art classes, the professor thumbtacked a blank sheet of paper to the cork board and asked us to “analyze and critique.” We were all confused at first, but collectively got the ball rolling, and it really opened our eyes to the possibilities of art in general. The size of the paper, the placement of the tack, the sheen and tone of the paper, how high on the wall the paper was, etc… All of what seemed to be nothingness, was really something in the building blocks of a piece of artwork.

What a great lesson. Maybe I’ll steal or adapt it!