Give your Weltanschauung a Workout

The Pegasus and the Pantograph.

Albert Einstein once said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

And if you teach English like me, you’ve seen your fair share of essays that open with Albert Einstein quotes.

The guy is just so quotable. Heck, that quote was a favorite of mine in the seventh grade, and I chose to make a poster of it for some project. See, I had drawn this pegasus in a notebook, and it struck me as the perfect illustration of “imagination.” And I guess my concept was to put it in some visual counterpoint to, like, a chalkboard full of math equations.

The problem was, I didn’t think I could replicate the pegasus on the posterboard. I had drawn it so perfectly in my notebook, and there was no way I could draw it that well again.

I explained the problem to my dad. An engineer at heart, he pulled out this old pantograph he had in the attic. He taught me how to use the simple machine to scale up my drawing by tracing over it with a stylus. Meanwhile a pencil attached to the other end of the device replicated my pegasus, twice as large.

But either the pantograph wasn’t quite calibrated, or we had the pegs in the wrong holes. The resulting copy of my pegasus was skewed. All stretched and distorted. Would it have come out better if I had heeded the quote I was trying to illustrate? used my imagination to solve the problem of drawing a larger pegasus? Rather than relying on my dad’s engineering knowledge?

Who knows. I let it be, and colored in the skewed pegasus. And that was that.

If I had stuck with the problem, I could have come out of the woods a better artist or a better engineer. I could have experimented, moved the pegs up and down the arms of the pantograph, failed in a variety of ways and eventually mastered the device. Or I could have sketched, freehand, many horses and birds, learning their construction, and solving the anatomical problem of how to attach wings on a horse.

“If I had stuck with the problem, I could have come out of the woods a better artist or a better engineer.”

But I didn’t. In the end that poster was a failure of both imagination and knowledge, because I failed to let myself fail.

A Theory from an Expert on Teacher Failure.

The fact is, my failure with that seventh-grade poster is just one failure in my illustrious career of failures. As a teacher, I’ve been failing magnificently for thirteen years now.

Sometimes I’m a great teacher. Sometimes I’m terrible. Sure I have good days and bad days, like everyone else, but it’s more than that. How do I explain that sometimes, my teaching undergoes total pedagogical breakdown, like I have no idea what I’m doing? Or that sometimes, I find myself in these transcendent moments of classroom flow?

I’m not saying I’m an Einstein, but I do have a theory. I think I suck so bad at teaching sometimes (but not others) because my pedagogical epistemology gets tired, like a weak or overworked muscle.

Pedagogical Epistemologies.

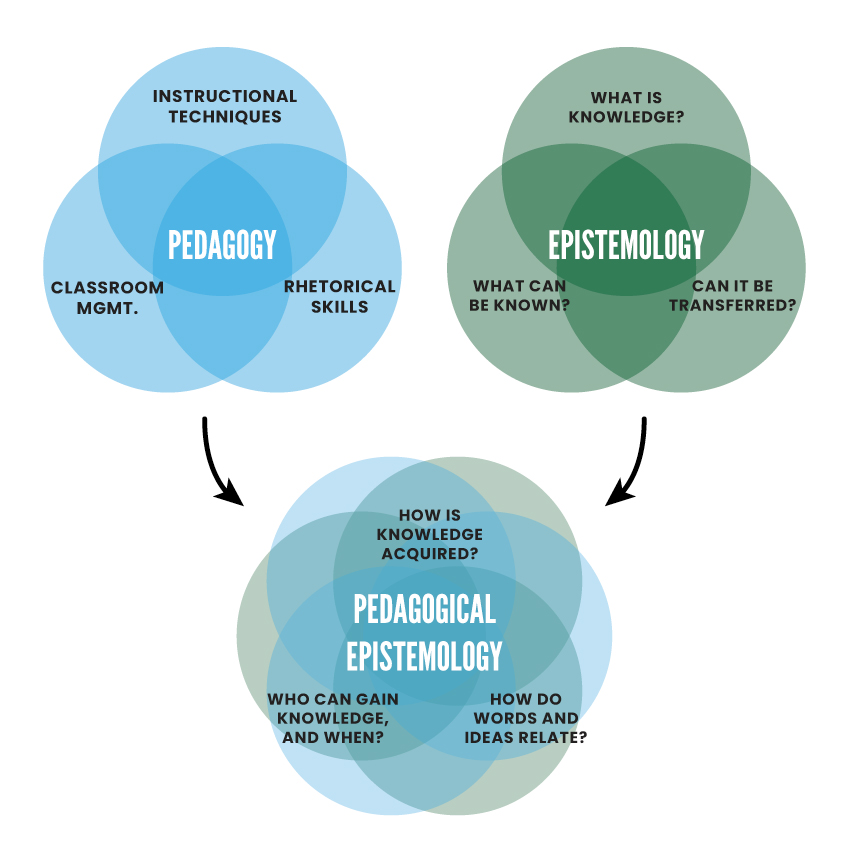

How do you like that heading? Ha. I know, sounds like the title to an impenetrable college textbook. The phrase needs some unpacking.

So, pedagogy is the science of teaching. Or art of teaching. Whichever you like. And epistemology is the theory of knowledge — how we know what we know, what knowing is, whether we can know anything.

But I’m going to be describing epistemologies –with an “s.” Differing, competing theories about knowledge. Different grids that we impose on the world to make sense of it.

If you put the terms together — pedagogical epistemologies — you are talking about different grids teachers impose on the world, to inform how and what they teach.

(If nothing else, I want you to think about this. As a branch of philosophy, for most people, epistemology is way out there. Sure. But for teachers, questions about how we know what we know, and whether we can know it, are essential to our day to day decisions in the classroom.)

Heck, let’s pull that out into a block quote:

“For teachers, questions about how we know what we know, and whether we can know it, are essential to our day to day decisions in the classroom.”

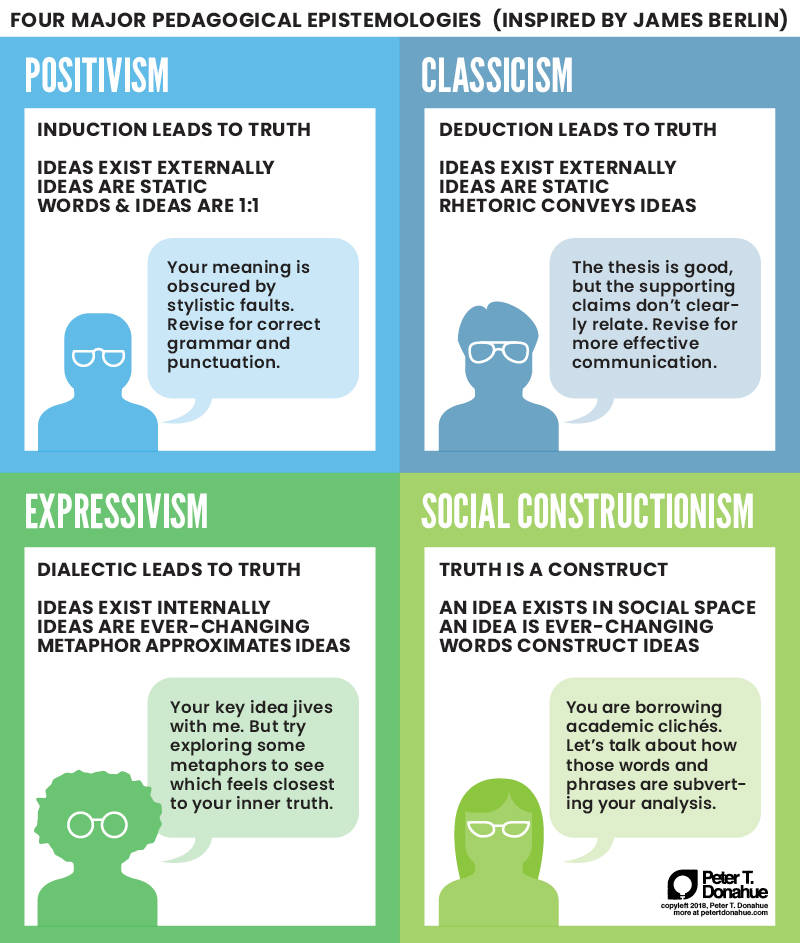

So, what epistemologies are you likely to encounter in the classroom? What views of reality? What Weltanschauungs? James Berlin, in his article “Contemporary Composition: The Major Pedagogical Theories,” does a great job of running down four of them.

Berlin saw that when teachers ask themselves, “How do you teach someone to write?” There are basically four ways to answer. Four major camps. And each camp believes fundamentally different truths about reality. About how knowledge is passed, and what it even is.

POSITIVISM

Positivist writing teachers place their faith in inductive reasoning. The truth can be discovered through observing and generalizing, and communicated using the correct language for the context.

So, the teacher in this paradigm is clearly a sage-on-the-stage type, concerned with correctness, fixing faults and helping students “adapt the discourse to its hearers” (Berlin) — the hearer being, in practice, the teacher.

So, let’s say a student wrote something like,

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the audience is not only taken through the story and elements of a tragedy, but through Shakespeare’s writing it becomes evident that Shakespeare made sure to include other ideas and dimensions to the story that developed the roles of secondary characters within the plot, displaying how they evolve and change throughout the development of the tragedy.

A positivist writing teacher might respond this way:

Your stylistic faults are interfering with the clarity of your ideas. The coordinative phrase “not only” must be followed by “but also.” Besides, you are trying to coordinate two syntactical structures that aren’t parallel. I advise you to restructure the sentence. Please also correct your stylistic issues: the use of passive voice (“it becomes evident”) and repetitive diction (“developed,” “development”).

CLASSICISM

Classicists are basically Aristotelian. So, in this camp, there’s a value placed on deductive reasoning, alongside inductive reasoning.

Aristotelian writing teachers are likely to treat the humanities and the sciences as fundamentally separate. Science arrives at certain truth inductively, and rhetoric does its best to approximate and communicate truth. (So, with classicism comes a certain disciplinary inferiority complex.)

Despite this reliance on deduction and rhetoric, however, the classicist sees language as basically unproblematic. Words mean what they mean.

So, given that same student-written passage–

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the audience is not only taken through the story and elements of a tragedy, but through Shakespeare’s writing it becomes evident that Shakespeare made sure to include other ideas and dimensions to the story that developed the roles of secondary characters within the plot, displaying how they evolve and change throughout the development of the tragedy.

A classicist writing teacher might respond this way:

Your claim that Shakespeare includes “ideas and dimensions” that develop secondary characters is rather self-evident, and therefore not a valuable premise to under-gird a literary analysis. It seems more promising to apply what we know of tragic structure to the plot and character, which you almost propose to do here. I suggest you focus your argument on applying one or two specific elements of Aristotelian tragedy.

EXPRESSIONISM

Berlin then describes expressionist or neo-Platonist teachers. The expressionist cannot rely on observation because the world is always changing.

But the truth, however hard to get at, must exist somewhere. The truth, says an expressionist, can be discovered through dialectic, but not communicated at all. Language can only approximate.

In other words, through talking something over, I can apprehend the truth internally, but I can’t put it into words for you; you need to apprehend it yourself. Expressionists therefore rely on metaphor and analogy as rhetorical strategies.

This perspective opens the opportunity for the writing teacher to value language for the messy thing it is — to value ambiguity, metaphor, revision. To value experimental poetry, freewriting, and discursive essays.

How would an expressionist teacher respond to this sample?

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the audience is not only taken through the story and elements of a tragedy, but through Shakespeare’s writing it becomes evident that Shakespeare made sure to include other ideas and dimensions to the story that developed the roles of secondary characters within the plot, displaying how they evolve and change throughout the development of the tragedy.

Maybe something like this:

I like how your sentence begins by considering the play from the perspective of the audience, but then sort of wanders into the writer’s perspective. It’s like you want to pick up the text like a prism and shine light into it from different angles. Why jam all that thinking into one sentence, though? Don’t rush it. Tease out the audience’s experience of the tragic plot elements. Walk me through it. Then move on to what you imagine Shakespeare was up to.

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM

All right, go get a cookie or something. Because this next one gets weird.

Berlin describes one more composition pedagogy theory, which was new enough in 1982 for him to call it New Rhetoric.

Since Berlin’s time, the epistemology behind New Rhetoric has come to be more clearly defined, and is usually called social constructionism.

For the other schools of thought, says Berlin, “truth exists prior to language so that the difficulty of the writer or speaker is to find the appropriate words to communicate knowledge. For the New Rhetoric truth is impossible without language since it is language that embodies and generates truth” and the writer is “a creator of meaning, a shaper of reality, rather than a passive receptor of the immutably given.” Berlin’s statements attempt to express just how fundamentally social constructionism breaks from all previous epistemology.

In the end, it proposes a view of reality counter to common sense. That’s super important, so we’ll come back to it later.

You know our little piece of student writing?

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the audience is not only taken through the story and elements of a tragedy, but through Shakespeare’s writing it becomes evident that Shakespeare made sure to include other ideas and dimensions to the story that developed the roles of secondary characters within the plot, displaying how they evolve and change throughout the development of the tragedy.

Here’s how a social constructionist teacher might reply:

You’re making some interesting moves: coordinative syntax (”not only…but…”), lots of hendiadys (”story and elements,” “ideas and dimensions,” “evolve and change”), even the length of the sentence (a whopping 59 words!). Here’s my guess: you’re spinning your wheels and trying to generate ideas, grabbing at scraps of academic-sounding sentences as they come to mind. Interesting how concerns about style are taking the reins as you work to develop your ideas about Macbeth. Why not try a different style, though: you could try writing like you were thinking aloud to a friend.

TL;DR.

Stages, not Camps.

So, here’s the thing. I love Berlin’s article. I’ve reread it pretty much every year since grad school. But I think his thinking is unfinished.

I don’t think there are four camps of writing teachers.

Berlin’s article encourages us to ask, “Which type of teacher am I? Postivist? Classicist? Expressionist? Social Constructionist?”

But that’s misguided.

In my experience, most of us fluctuate. We find ourselves, on any given day, hopping all over the philosophical map. As Montaigne said, “we are all patchwork.” Or “we are unformed lumps.” Depends on the translation.

In my view, Berlin’s pedagogical epistemologies aren’t four competing schools of thought. They’re not bins teachers sort into. They’re more like steps on a slippery staircase.

In fact, I’d argue these epistemologies are part of a developmental stage model. In other words, a human being can grow and improve, reaching the next level. And is expected to, if all goes well physically and socially. But in times of strain or trauma, a person can slide back to the previous level.

The Takeaway.

Let’s come back to the muscle analogy. Cognitive dissonance, again, is the mental nails-on-a-chalkboard we experience when our ideas don’t match the reality we’re presented with. It’s a strain on our mental resources, just like lifting a weight is a strain on our muscles. Exercise can build stamina. Your epistemology, like a muscle, gets stronger the more it is exercised, and can lift more cognitive dissonance.

To sum up my experience: my failure or success as a teacher is related to how much cognitive dissonance I’m able to handle in the moment. What’s the takeaway? To be a better teacher, that tolerance is what I need to try and build up.

If I’m having a bad day, or I’m real hangry, I slip backward into positivism. If I’m in one of those magical hours of student-centered, classroom flow, asking all the right questions — if I’m running on the social constructionist OS — I’ve probably had a good night’s sleep for once.

So, in the end, I think what I’ve discovered is this. While good teaching relies on reading, discussing, and practicing research-based ideas, on trusting the creative process, on integrating feedback from your students, on social constructionism — consistent good teaching means developing the cognitive stamina to keep believing all that when things don’t look like they’re going great.

What’s your experience been, as a teacher or a student? Do you feel like your view of reality affects the quality of your work? And is affected by your mood or stamina? I’d love to hear from you.

Also, here’s the link to that handout again, in case you’re interested!